Disclaimer:

This article is NOT explaining what your training volume should be.

It is simply explaining the complications of measuring volume in the Sport of Fitness and the systems that I personally have found useful for overcoming these obstacles.

Defining Volume

Volume is simply the amount of training an athlete is doing.

Gillian ran 10 miles. That’s her volume.

In that respect things are straight forward.

However, knowing Gillian ran 10 miles isn’t super helpful for her coach who is trying to construct her training plan. It leaves a lot of unanswered questions…

Did she run the 10 miles all at once? What pace did she run at? Was that more or less than last time? What is she preparing for? When is her next competition?

Let’s take a closer look at the factors we need to consider when measuring volume…

Volume is always in respect to time.

Mike cycles 8-10,000 Miles per year.

Linda swims 2-3km per session.

Jamie squats 15-20 sets per week.

Volume is only useful to the coach if it is in respect to time.

Ben’s Recommendation:

Please Note: “Ben’s Recommendations” will be directed towards CrossFit Athletes.

I recommend tracking volume by the microcycle, which is the smallest block of training. For most people, this is a week of training. They look at their previous week of workouts and their training results, to know how to progress their training appropriately. You might choose to track volume within a specific workout / session in addition to the week, but the weekly microcycle (for most coaches and athletes) is a good place to start.

Volume is pattern specific.

Mike cycles 8-10,000 Miles per year.

Linda swims 2-3km per session.

Jamie squats 15-20 sets per week.

Now, not everyone tracks volume this way, but I believe it is the most useful.

For example, Jamie could have reported lifting 127,000 pounds last week. That included squat, bench, deadlift and accessories. And that included his warm-ups and building sets.

However, looking at that number it’s really hard to know how to progress Jamie’s training.

Ben’s Recommendation:

Don’t track every single movement in CrossFit.

That’s a recipe for “losing the forest in the trees.” That process would be exhausting, time consuming and unproductive.

Rather, measure the volume of each category of movement pattern.

For example, I track Hanging Gymnastics, Inverted Gymnastics, Bounding Movements, Hinging, Squatting, and Overhead Lifting. Every movement I prescribe to my athletes fits into one of those categories.

Now I no longer have to track Chest-to-Bar, Toes-to-Bar, Bar Muscle-Up and Ring Muscle-Up…I can just track hanging gymnastics reps / contractions.

Are there limitations to this process? Absolutely.

But it’s a system that I’ve found works for me.

Volume is always in relationship to intensity.

The reason coaches and athletes track volume is to see how it impacts performance.

And since we are talking about an impact on performance and recovery, we can’t talk about volume without talking about intensity.

Running 30 Miles per week at your Half Marathon pace is much different than running 30 miles per week at your Mile Time Trial pace. The former could be a deload for many runners, where the latter would leave almost all athletes trashed.

And let’s say a powerlifter accumulates 40 sets per week of bench press. If they do so by hitting low percentage sets and stopping before fatigued, that’s completely different than hitting rep maxes in the 75-85% range.

This is why for volume to be a worthwhile metric to track it needs to be with respect to intensity.

Ben’s Recommendation:

Let me build upon the movement pattern tracking system I use.

First of all, many of the gymnastics movements are have little variation to their intensity, so tracking gross volume (# of reps) actually isn’t a problem. Sure you might want to keep track if most the volume is more taxing variations (ie. muscle-ups or legless rope climbs), but if you are hitting a balance of The Big Five on a weekly basis, it shouldn’t be an issue.

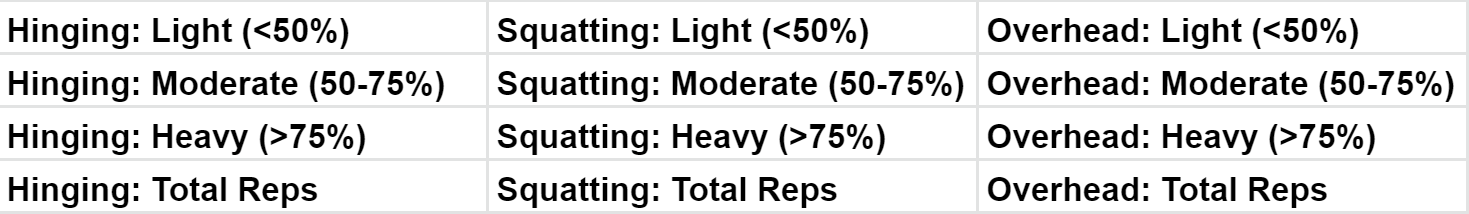

For Weightlifting Work, I track the volume (as contractions / reps) in each movement pattern in three intensity zones: Light (<50%), Moderate (50-75%), and Heavy (>75%). Again, there are limitations to this…for example, a Snatch @ 75% is not equal to a snatch @ 93%, but again that which is practical and simple is better than a “perfect” system that is too complicated to use.

Typically, “Light” weights are often cycled Touch-N-Go for athletes in MetCons. “Moderate” weights are most often singles in MetCons and possible TnG in Interval formats, like EMOMs. And “Heavy” weights are most often percentage work, more focused on 1RM development.

Tracking (1) Hinging, (2) Squatting, and (3) Overhead movements in each of these three loading intensity zones has been my go-to system for tracking volume with respect to intensity.

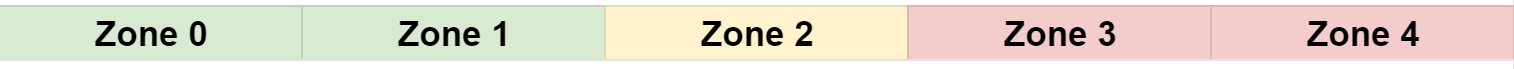

For Conditioning Work, I often track the estimated time in the Heart Rate Zone. I adopt my five Zone System (Z0 – Z4) to three zones, just to simply it and have it mirror the Weightlifting tracking system. I call them Green, Yellow and Red, and here’ how they correlate with the five zone model…

For each relevant MetCon, cyclical or interval style piece I write, I estimate where that athlete will spend the majority of their time, then add it to the green, yellow or red zone.

Yet again, it’s an imperfect system with plenty of guess work, but it serves its purpose: identify holes in the programming that I overlooked in the “rough draft.”

For example, if I see an athlete is projected to spend 75 minutes one week in the red zone (Z3-Z4), I know that’s a recipe for them to get burned out and have performance and recovery status drop.

In general, I’m very calculated and mindful of how much “Red Zone” work I give an athlete, and I’m also very mindful to give them a minimal dose of “Green Zone” easy work to contrast it. Often the “Yellow Zone” is more a product of different types of interval work, which I keep an eye on more so through regulated volume in the other movement categories.

Volume is always in relationship with density.

Just like intensity, density is a crucial factor to track, especially as it is in relation with volume.

Often athletes and coaches want to blame volume for DOMS and joint irritation, but in the Sport of Fitness, it’s more often the result of accumulating moderate volume at a high movement density (reps / minute).

Ben’s Recommendation:

Since both volume and density pose potential for high muscle and joint irritation, I like to seesaw volume and density: as one trends up the other trends down.

If I am building an athlete to CrossFit Open Functional Volume in The Big Five, then I’m probably having them do so in a low density format.

Once they finish their volume build, then I’ll reduce volume slowly as density builds.

Obviously during a volume progression, you should be tracking volume. But I would recommend continuing to track volume through the density progression as well, making sure that volume is backed off at an appropriate rate, based on how quickly density is being built.

Here would be a very simple volume and density progression…

Week 1

Every 2 Minutes x 6 Sets: 10 Chest-to-Bar Pull-Ups

[Volume = 60] [Density = 5 reps / min]

Week 2

Every 2 Minutes x 8 Sets: 10 Chest-to-Bar Pull-Ups

[Volume = 80] [Density = 5 reps / min]

Week 3

Every 2 Minutes x 10 Sets: 10 Chest-to-Bar Pull-Ups

[Volume = 100] [Density = 5 reps / min]

Week 4

Every 2 Minutes x 12 Sets: 10 Chest-to-Bar Pull-Ups

[Volume = 120] [Density = 5 reps / min]

Week 5

Every 1:30 x 10 Sets: 10 Chest-to-Bar Pull-Ups

[Volume = 100] [Density = 6.7 reps / min]

Week 6

Every 1:15 x 9 Sets: 10 Chest-to-Bar Pull-Ups

[Volume = 90] [Density = 8 reps / min]

Week 7

Every 1:00 x 8 Sets: 10 Chest-to-Bar Pull-Ups

[Volume = 80] [Density = 10 reps / min]

Week 8

Every 0:45 x 7 Sets: 10 Chest-to-Bar Pull-Ups

[Volume = 70] [Density = 13.3 reps / min]

Thinking about volume inhibits artistic program design.

The last point I want to make is that if you become hyper focused on tracking volume (or any other metric), it will likely make you worse at creating well-rounded, effective programming.

The best coaches are artists and scientists.

That statement has many layers to it, but for this discussion it means that you can be running some linear progressions while simultaneously programming some non-linear pieces.

For example, you could run the Chest-to-Bar progression I outline above on one day and another day could be a MetCon that is changing each week (non-linear) that mimics the testing body of the sport, but is dreamt up out of your imagination.

Ben’s Recommendation:

For all clearly defined progressions (whether linear or otherwise), creativity isn’t needed. It’s easy to build these items out week over week, adjusted as needed. So for these elements of the program, I would consider and calculate volume during the programming process.

For those items that come out of your creativity and are non-linearly in nature, I would first write those elements, and then go back after the fact and determine the volume of them, making adjustments where you see the volume is “out of bounds.”

Volume Data Analysis using a Sample Week of Training

Here is the week of training of Feb. 8, 2021 from The Protocol, which I analyzed for volume data.

If you are new to this process of tracking volume, it will take some time to set up and get used to. For me, it only adds a few minutes to the process of building out each of my individual design athletes programs.