Are you strong enough?

Strength is a big topic in the Sport of Fitness and rightly so.

The bottom line is you must have at least the minimal numbers to be able to compete at a certain level. And likely (but not always) improving your strength number means that moving fixed weights (e.g. 135/95lbs) becomes easier because it’s now a lesser percentage of your max.

These numbers are generally well known in the community. For example, if you failed to make the final bar in 17.3 (265/185lbs), you probably also failed to punch a ticket to the Games.

However, because these numbers are such clear standards, it’s easy to get fixated on your maxes.

Don’t get me wrong, your strength numbers (absolute metrics) matter.

But there’s something just as important that rarely gets talked about: strength ratios.

What are strength ratios?

Basically, strength ratios are a comparison between how strong you are in one lift relative to how strong you are in another.

For example, let’s say your back squat is 350 and your front squat is 300. This means your front squat is 86% (that’s the strength ratio) of your back squat.

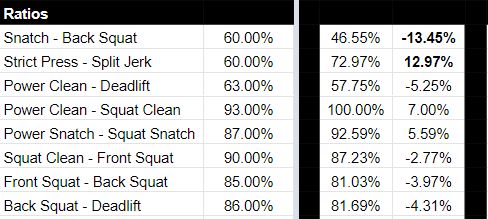

Essentially, you go through a list of exercises, comparing two at a time, and you are seeing if each is within an acceptable range.

For example, we know it is ideal for an athlete’s front squat to be ~85% of their back squat. Since your front squat is 86% of your back squat, good news, you’re well within the +/- 5% of wiggle room I give for strength ratio metrics.

What does it mean if I’m out of range?

Now, let’s pretend we have a different athlete: Mike. Mike back squats 390lbs and yet his front squat is the same as you: 300lbs. That means that his ratio is 77%, which is -8% from the ideal. This means that Mike can’t showcase his leg strength, he has poor t-spine / front rack mobility, or he has some other restriction that is preventing him from expressing his potential. In short, Mike doesn’t need to back squat more, he needs to be able to front squat a higher percentage of his back squat.

Then there’s Frank. While Frank only back squats 325, his front squat PR is still 300, like the other two athletes. This means that his strength ratio is 92%, which is +7% above the ideal. Likely if Frank wants to front squat more, he needs to improve his back squat.

And we can continue…line by line…moving through the 8 total metrics for strength ratio.

Lastly, you’ll notice that there is a second column for absolute numbers.

This is where you compare your strength numbers relative to the field you want to compete against…Elite Females, Masters 35-39, etc.

Detailed Interpretation of Your Results

(1) Snatch – Back Squat

This is -firstly- a look at absolute strength (powerlifting) versus speed strength (weightlifting). Absolute strength (squat, deadlift, strict press) involves higher systemic tension and is less technical in nature. That leads to the other thing this is testing: skill. How technical, skillful and efficient are you relative to your strength? Those who have a low percentage here likely need more technical development on the Olympic Lifts, and possibly exhibit lower levels of elasticity and joint freedom.

(2) Strict Press – Split Jerk

The first thing this is comparing is your static vs. dynamic pressing ability. Are you better at generating force at higher or lower joint velocities? How developed is your upper body compared to your leg drive? How efficiently can you transfer power through High-Support Positions to support heavy loads overhead?

(3) Power Clean – Deadlift

This is measuring your hinging strength versus your explosive hip extension. However, leg strength and technique also play roles. An athlete with a low ratio might have poor positions or technique, but they might also have a weak squat that prevents them from catching near parallel without being buried by the weight.

(4) Power Clean – Squat Clean

This is your hip extension ability versus your leg strength. Note that on several of these items (this one included) the numbers may be swayed slightly based on an athlete’s anthropometrics (e.g. mass distribution, limb lengths, etc). For example, a long-limbed athlete will often be able to power nearly as much as they can squat.

(5) Power Snatch – Squat Snatch

This measures hip extension versus mobility, overhead stability and efficiency. Often inefficient lifters will pull a bar much higher than they need to when performing squat snatches or cleans. For example, you should only need to pull a snatch to belly button height to make the lift if you have a quick turnover and good overhead squat mobility.

(6) Squat Clean – Front Squat

This is a measurement of weightlifting skill and efficiency, relative to leg strength. A precisely timed pull is needed to place the bar in the right location (forward / back), as well as the position and timing in space. Too early and the bar will crash on you, too late and you will never get under the bar in time. This are are areas that an inefficient, yet strong, lifter can improve.

(7) Front Squat – Back Squat

This is the example I used in the introduction. Again, front rack position, t-spine extension and torso orientation will all impact an athlete’s ability to front squat a high percentage of their back squat.

(8) Back Squat – Deadlift

This is a rough look at leg strength versus back strength and hinging ability. Once again, anthropometrics will play a significant role. Athletes with long femurs will often have a significantly higher deadlift than back squat and short-limbed / femured lifters will find squats more comfortable and the positions strong. So, yes the ratios might have some room for individuality, so this information is best to be combed over by an experienced coach.

If you’re looking for one of those, I got you.

Using Strength Ratios to Allocate Training Resources

Every athlete has finite training resources. I’ve referred to this before as “adaptation currency.” You can only spend so much before you’re broke or go into debt. Neither of those is ideal. So as you train under your MRV (max recoverable volume), how will you spend your precious resources?

That’s a question that isn’t asked often enough. Too often athletes just want to add more and more into their training. I think most athletes who are striving to be the best they can fall into this at some point or another. Just remember…

More isn’t better. Better is better.

For example, let’s take the following athlete.

Clearly this athlete has some limitations that are preventing them from dynamically claiming a solid overhead position in both snatches and jerks.

So, I would start with a movement screen and voilà, there’s clearly limitations with shoulder mobility.

So for this athlete, this training time (and adaptation currency) will be best spent by building the high-support positions needed and hammering their mobility…and NOT spending lots of time working strict pressing strength and pressing accessory work.

Remember, what you choose not to do is likely (if not more) important than what you choose to do.

I hope you found this self-analysis helpful. If you need help interpreting your results, look into getting an in-depth assessment. It’s something that I take all of my 1-on-1 Remote Coaching clients through before we begin the real work.